Since I use the free version of WordPress, I subject myself to its practice of randomly interspersing ads in my posts as well as providing additional links to (weird) content at the end. Sadly, I do not have any control over what WP decides to foist upon my posts. Thus, if anything appears that is ridiculous, unseemly, tawdry, controversial, and/or contrary to my character and beliefs, please know two things: (1) I don’t endorse it, and (2) I loathe ads—especially when they disrupt the flow of a post.

in the words of Doc Holliday…

“Oops.”

While reading through Robert Anderson’s book, The Bible or the Church? (1908), there was a passing comment on the sacraments. One that succinctly addressed a fundamental flaw in the usual thinking about the sacraments—namely, the Lord’s Supper (or the Eucharist). Anderson simply said:

“A sacrament is merely a sign or symbol to represent some spiritual reality. In the Eucharist, for example, the bread is bread and nothing more, but it represents the Lord’s body. If therefore the bread be regarded as being in fact His body, it is no longer a ‘sacrament’ at all” (2)

Thus, according to Anderson’s (good) logic, only those who see the sacrament for what it is can call it what it is. But those who believe the sacrament to be more than it is are—in word and practice—devaluing not only what they believe but also what they venerate. Yet, that’s only a part of the problem.

Because the ideas are more valuable than the truth, such adherents not only “twist facts to suits theories, instead of theories to suit facts,”1 but also twist meanings to suit preferences. Specifically, they will redefine the term “recession” “sacrament” so that it legitimizes the desired narrative, and will forbid any push-back or criticism against the new definition. In fact, anyone who believes and/or speaks contrary will be not just shamed but also cursed as being evil.

______________________________________

1 A.C. Doyle, “A Scandal in Bohemia,” in The Complete Works of Sherlock Holmes (Barnes & Noble, 2012), 1.179.

viewing list of 2023

Those who know me know that I enjoy not only books but also movies. Not too long ago, my daughter asked me how many movies I’ve seen in my lifetime, and I tentatively guessed “about 1000.”* She also asked me how many of those are worth rewatching, and I said “About 75%,” to which I added: “And about 50% of those are worth rewatching more than once. And about 25% of those are worth watching incessantly.” So, just for kicks and giggles, here’s the list of what I watched in 2023—and not just movies, but also documentaries(º) and comedy specials:

- Strategic Air Command (1955)

- The Saturn V Story (2014)º

- Master and Commander (2003), rewatch

- Sebastian Maniscalco: What’s Wrong with People? (2012)

- Sebastian Maniscalco: Is It Me? (2022)

- Hobbit: Desolation of Smaug (2013)

- Hidalgo (2004), rewatch

- Brian Regan: On the Rocks (2021)

- Bourne Identity (2002), rewatch

- Jungle Cruise (2021)

- Iron Man (2008), rewatch

- Great Escape (1963), rewatch

- Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), rewatch

- Bourne Supremacy (2004), rewatch

- Tombstone (1993), rewatch

- Bourne Ultimatum (2007), rewatch

- Clue (1985), rewatch

- Spider-Man 3 (2007)

- Minions: The Rise of Gru (2022)

- Pirates of the Caribbean: Curse of the Black Pearl (2003), rewatch

- Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest (2006), rewatch

- Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End (2007), rewatch

- Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe (2005), rewatch

- O, Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000), rewatch

- Man in the Iron Mask (1998), rewatch

- Drunken Master (1978)

- Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales (2017), rewatch

- Chronicles of Narnia: Prince Caspian (2008)

- Willow (1988), rewatch

- National Treasure (2004), rewatch

- Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides (2011), rewatch

- Sebastian Maniscalco: Aren’t You Embarrassed? (2014)

- Ivan the Terrible (2014)

- Lost Treasures of Egypt: Curse of the Afterlife (2019)º

- Lost Treasures of Egypt: Mystery of Tut’s Tomb (2021)º

- Lost Treasures of Egypt: Legend of the Pyramid Kings (2021)º

- Lost Treasures of Egypt: Ramses Rise to Power (2021)º

- iRobot (2004), rewatch

- One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (1970)

- Lost Treasures of Egypt: Pyramid Tomb Raiders (2021)º

- Chronicles of Narnia: Voyage of the Dawn Treader (2010)

- Fletch (1985), rewatch

- The Mask of Zorro (1998), rewatch

- The Sting (1973)

- Bourne Legacy (2012), rewatch

- Lost Treasures of Egypt: Cleopatra, Egypt’s Last Pharaoh (2021)º

- Lost Treasures of Egypt: Tutankhamun’s Unsolved Secrets (2021)º

- Thor: Love and Thunder (2022)…waste of time

- Black Panther (2018)

- Lost Treasures of Egypt: Tutankhamun’s Treasures (2019)º

- Lost Treasures of Egypt: Hunt for the Pyramid Tomb (2019)º

- The Rundown (2003), rewatch

- Lost Treasures of Egypt: Cleopatra’s Lost Tomb (2019)º

- Guardians of the Galaxy (2014)

- Conan the Destroyer (1984), rewatch

- Rise of the Black Pharaohs (2016)º

- Fletch Lives (1989), rewatch

- Guardians of the Galaxy, vol. 2 (2017)

- Star Wars: A New Hope (1977), rewatch

- Eraser (1996), rewatch

- Star Wars: Empire Strikes Back (1980), rewatch

- It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963)

- Star Wars: Return of the Jedi (1983), rewatch

- Star Wars: Force Awakens (2015), rewatch

- Star Wars: Solo (2018), rewatch

- Hot Fuzz (2007)

- Avengers (2012), rewatch

- Incredible Hulk (2008)…the best part was the cameo of Lou Ferrigno

- Top Gun: Maverick (2022), rewatch

- Doctor Strange (2016), rewatch

- American Sniper (2014)

- Charade (1963), rewatch

- To Catch a Thief (1955)…not impressed…at all

- The Angry Red Planet (1959)

- Star Wars: Phantom Menace (1999), rewatch

- Star Wars: Attack of the Clones (2002), rewatch

- MacArthur (1977), not impressed

- The Final Countdown (1980)…definitely MST3K worthy

- Jim Gaffigan: Dark Pale (2023)

- RED (2010), rewatch

- Gladiator (2000), rewatch

- RED 2 (2013), rewatch

- Batman (1989), rewatch

- Star Wars: Rogue One (2016), rewatch

- Captain Marvel (2019), rewatch

- A Series of Unfortunate Events (2004), rewatch

- Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (2001)

- Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (2002)

- Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004)

- Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (2005)

- Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (2007)

- Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince (2009)

- Tut’s Treasures: Hidden Secrets. Treasures Rediscovered (2018)º

- Tut’s Treasures: Hidden Secrets. Golden Mask (2018)º

- Lost Treasures of Egypt: Hunt for Queen Nefertiti (2020)º

- Tut’s Treasures: Hidden Secrets. Golden Mask (2018)º

- National Treasure 2 (2007), rewatch

- Thor: Dark World (2013), rewatch

- Christmas Vacation (1989), rewatch

- Holiday Inn (1942), rewatch

- White Christmas (1954), rewatch

- Guardians of the Galaxy, vol. 3 (2023)…waste of time

- Iron Man 2 (2010), rewatch

- Home Alone (1990), rewatch

- Home Alone 2 (1992), rewatch

- His Only Son (2023)…decent, but a tad too dramatic and quite a bit slow

- Back to the Future (1985), rewatch

__________________________________________

* In the months that followed her question, I decided to see how close my guess was to reality. At present, the count is 1,085. But I have hunch that’s not entirely complete. I’m sure there are others that I’ve forgotten that I’ve seen. And if one’s curious: since c.2012, I’ve read close to 500 books. That’s about 1/8 of my personal library, which I’m trying to read through—with the exception of a few options.

reading list of 2023

This year was slightly better than last in the category of books (but still less than my intended goal), and extensively better in the category of articles, essays, etc. I’m already looking forward to next year’s lineup (which is partially random choice!) and learning more. Without further ado, here is the list of things read in 2023 (and you’ll see a new category, which was fun to experience):

Books (and booklets):

- Leo Tolstoy, Resurrection (1966)

- Tom Clancy, The Cardinal of the Kremlin (1988)

- Hugh McNeile, Three Sermons Preached before the Judges, at the Assizes Held in the County of Surrey, in the Year 1826 (1826)

- Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (1970)

- James R. White, Mary—Another Redeemer? (1998)

- P.G. Wodehouse, Plum Pie (1966)

- Thomas Malory, King Arthur and His Knight (1927)

- D.L. Moody, Heaven (1884)1

- James Fennimore Cooper, The Last of the Mohicans (2004 edition)

- D.A. Carson, The King James Debate: A Plea for Realism (1978)

- Robert Ludlum, Road to Omaha (1992)

- Köstenberger, Andreas J. & Michael J. Kruger, The Heresy of Orthodoxy. How Contemporary Culture’s Fascination with Diversity Has Reshaped Our Understanding of Early Christianity (2010)2

- Richard Philips, 500 Questions on the New Testament (1820)

- Mary Shelley, Frankenstein (1992)

- Horace L. Hastings, The Corruptions of the New Testament (1884)3

- Samuel P. Tregelles, The Hope of Christ’s Second Coming. How Is It Taught in Scripture, and Why? (1864)4

- Neil R. Lightfoot, How We Got the Bible (2003)

- Chaim Potok, I Am Clay (1992)

- Isaac M. Haldeman, Theosophy or Christianity: Which? A Contrast (1893)

- C. Norman Kraus, Dispensationalism in America: Its Rise and Development (1958)

- Robert D. Wilson, The Present State of the Daniel Controversy (1919)5

- T.J. Betts, How to Teach the Old Testament to Christians (2023)

- Cleland B. McAfee, The Greatest English Classic. A Study of the King James Version of the Bible and Its Influence on Life and Literature (1912)

- Plutarch, The Makers of Rome: Nine Lives (1965)

- Bede, A History of the English Church and People (1955)

- H.A. Ironside, The Mormon’s Mistake, or What is the Gospel? (1896)

- Jack Cottrell, “Covenant and Baptism in the Theology of Huldreich Zwingli” (unpublished PhD thesis, 1971)

- P.G. Wodehouse, Uncle Fred in the Springtime (1939)

Books (read with the daughter):

- Roald Dahl, George’s Marvelous Medicine (2007)

- C.S. Lewis, The Magician’s Nephew (1955)

- C.S. Lewis, The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe (1950)

- C.S. Lewis, The Horse and His Boy (1954)

- C.S. Lewis, Prince Caspian (1951)

- C.S. Lewis, The Dawn Treader (1952)

- C.S. Lewis, The Silver Chair (1953)

- C.S. Lewis, The Last Battle (1956)

- Donald J. Sobol, Encyclopedia Brown Saves the Day (1970)

- Donald J. Sobol, Encyclopedia Brown, Boy Detective (1963)

- Louis Sachar, Sideways Stories of Wayside School (1985)

- Louis Sachar, Wayside School is Falling Down (1989)

- Mary Jane Auch, I Was a Third Grade Spy (2003)

- Herman Parish, Amelia Bedelia: Unleashed (2013)

- Herman Parish, Amelia Bedelia: Shapes Up (2014)

- Donald J. Sobol, Encyclopedia Brown Tracks Them Down (1971)

Articles, essays, etc.:

- David Gakunzi, “The Arab-Muslim Slave Trade: Lifting the Taboo,” Jewish Political Studies Review, online article (Sept, 2018)

- Brian Jones, “3 Church Attendance Shifts Troubling Senior Pastors,” Senior Pastor Central blog (no date)

- Brian Jones, “Spit Out the Lotus Plant (or Thoughts on Why Going to Church Matters),” blog post (April, 2015)

- Brian Jones, “I’m Not Being Fed (and Other Stupid Things Christian Say),” blog post (April, 2015)

- Louis M. Profeta, “Your Kid and My Kid Are Not Playing in the Pros,” Nuvo online article (March, 2014)

- Cecil Maranville, “The Rapture: A Popular but False Doctrine,” online article (Sept, 2008)

- Cecil Maranville, “The Rapture is Wrong: The Saints Don’t Rise to Run Away,” online article (Nov, 2008)

- Timothy Berg, “The Preface to the Greek TR of F.H.A. Scrivener,” King James Bible History online article (March 2020)

- Timothy Berg, “Hampton Court—Avenue and Dates,” King James Bible History online article (December 2020)

- Timothy Berg, “Hampton Court—Attendees,” King James Bible History online article (December 2020)

- Timothy Berg, “Hampton Court—Barlow’s Vindication and Extant Sources,” King James Bible History online article (December 2020)

- Crawford Gribben, “Wrongly Dividing the Word of Truth: The Uncertain Soteriology of the Scofield Reference Bible,” Evangelical Quarterly 74.1 (2002): 3–25

- Dustin Benge, “Help! I Love Jesus but not the Church,” Crossway online article (March 2022)

- Hugh Henry & Daniel Dyke, “Israel’s Sojourn in Egypt and How It Affects Calculations of a Creation Date, part 1,” Reasons to Believe web article (September, 2013)

- Hugh Henry & Daniel Dyke, “Israel’s Sojourn in Egypt and How It Affects Calculations of a Creation Date, part 2,” Reasons to Believe web article (September, 2013)

- Jermain Rinne, “5 Common Ways Church Members Go Astray,” Crossway online article (May, 2022)

- G.L. Priest, “A.C. Dixon, Chicago Liberals, and The Fundamentals,” Detroit Baptist Seminary Journal 1 (1996): 113–34

- John Millam, “Historic Age Debate: Overview, part 1,” Reasons to Believe web article (October, 2007)

- John Millam, “Historic Age Debate: Overview, part 2,” Reasons to Believe web article (October, 2007)

- William Lane Craig, “Doctrine of Creation (Part 1): Creatio Ex Nihilo,” Reasonable Faith podcast transcript (2018)

- William Lane Craig, “Doctrine of Creation (Part 2): Does Genesis 1 Teach Creatio Ex Nihilo?,” Reasonable Faith podcast transcript (2018)

- Charles E. Smith, “The Purpose of the Apocalypse,” Bibliotheca Sacra 78.310 (1921): 164–71

- Stephen D. Snobelen, “A Time and Times and the Dividing of Time: Isaac Newton, the Apocalypse, and 2060 A.D.,” Canadian Journal of History 38 (2003): 537–51

- William H. Green, “Primeval Chronology: Are There Gaps in the Biblical Genealogies?” Bibliotheca Sacra 47.186 (1890): 285–303

- Jeffrey Breshears, “How Young-Earth Creationism Became a Core Tenet of American Fundamentalism, part 1,” Reasons to Believe web article (December, 2013)

- Jeffrey Breshears, “How Young-Earth Creationism Became a Core Tenet of American Fundamentalism, part 2,” Reasons to Believe web article (January, 2014)

- W. Sibley Towner, “Rapture, Red Heifer, and Other Millennial Misfortunes,” Theological Table Talk 56.3 (1999): 379–89

- Gilman, Edward W., “Early Editions of the Authorized Version of the Bible,” Bibliotheca Sacra 16.61 (1859): 56–81

- Rodney J. Decker, “The Rehabilitation of Heresy. ‘Misquoting’ Earliest Christianity” (paper delivered at Central Baptist Seminary, for the Bible Faculty Summit, 2007)6

- Timothy Berg, “Hampton Court—Activities, Day 1,” King James Bible History online article (Sept 2022)

- Timothy Berg, “Hampton Court—Activities, Day 2,” King James Bible History online article (Oct 2022)

- Timothy Berg, “Hampton Court—Activities, Day 3,” King James Bible History online article (Oct 2022)

- Hugh Henry & Daniel Dyke, “From Noah to Abraham: Evidence of Genealogical Gaps in Genesis, part 1,” Reasons to Believe web article (July, 2012)

- Hugh Henry & Daniel Dyke, “From Noah to Abraham: Evidence of Genealogical Gaps in Genesis, part 2,” Reasons to Believe web article (July, 2012)

- Hugh Henry & Daniel Dyke, “From Noah to Abraham: Evidence of Genealogical Gaps in Genesis, part 3,” Reasons to Believe web article (July, 2012)

- Hugh Henry & Daniel Dyke, “From Noah to Abraham: Evidence of Genealogical Gaps in Genesis, part 4,” Reasons to Believe web article (August, 2012)

- Hugh Henry & Daniel Dyke, “From Noah to Abraham: Evidence of Genealogical Gaps in Genesis, part 5,” Reasons to Believe web article (August, 2012)

- Hugh Henry & Daniel Dyke, “Biblical Genealogies Revisited: Further Evidence of Gaps,” Reasons to Believe web article (November, 2013)

- Francois R. Möller, “A Hermeneutical Commentary on Revelation 20:1–10,” In die Skriflig 53.1 (2019)

- D.A. Carson, “The New English Bible: An Evaluation,” Northwest Journal of Theology 1.1 (1972): 3–14

- Hugh Henry & Daniel Dyke, “Did Vertebrate Animals Die Before the Fall of Man?,” Reasons to Believe web article (September, 2014)

- J. De Jong, “Luther’s Little Jewel,” Spindle Works (1996), online article

- J. Faber, “The Catholic Character of the Church,” Spindle Works (2001), online article

- John Millam, “Coming to Grips with the Early church Fathers’ Perspective on Genesis, part 1,” Reasons to Believe web article (September, 2011)

- John Millam, “Coming to Grips with the Early church Fathers’ Perspective on Genesis, part 2,” Reasons to Believe web article (September, 2011)

- John Millam, “Coming to Grips with the Early church Fathers’ Perspective on Genesis, part 3,” Reasons to Believe web article (September, 2011)

- John Millam, “Coming to Grips with the Early church Fathers’ Perspective on Genesis, part 4,” Reasons to Believe web article (September, 2011)7

- John Millam, “Coming to Grips with the Early church Fathers’ Perspective on Genesis, part 5,” Reasons to Believe web article (October, 2011)

- Hugh Henry & Daniel Dyke, “Evening and Morning and Entropy in Creation?,” Reasons to Believe web article (November, 2022)

- John Millam, “Historic Age Debate: Dependence on Translations, part 1,” (June, 2009)8

- John Millam, “Historic Age Debate: Dependence on Translations, part 2,” (June, 2009)

- John Millam, “Historic Age Debate: Dependence on Translations, part 3,” (July, 2009)

- John Millam, “Historic Age Debate: Dependence on Translations, part 4,” (July, 2009)

- John Millam, “Historic Age Debate: Dependence on Translations, part 5,” (July, 2009)

- Arthur Metcalf, “The Parousia Versus the Second Advent,” Bibliotheca Sacra 64.253 (1907): 51–65

- Chris Smith, “The Idolatry of Worship Service Flow,” Lifeway Research online article, (August, 2023)

- Martin Heide, “Erasmus and the Search for the Original Text of the New Testament,” Text & Canon Institute online article (February, 2023)

- Meredith G. Kline, “Har Magedon. The End of the Millennium,” JETS 39.2 (1996): 207–22

- Daniel Wallace, “Do Manuscripts of Q Still Exist,” blog post (January, 2013)9

- Nathan Rose, “5 Spiritual Dangers of Skipping Church,” ChurchLeaders online article (May, 2023)

- Randy Brown, “David Norton Interview,” Bible Buying Guide online article (July 2017)

- James White, “What Really Happened at Nicea?,” Christian Research Institute online article (Spring, 1997)

- Timothy Berg, “The Five Types of Marginal Notes in the King James Bible,” King James Bible History blogpost (March, 2020)

- Timothy Berg, “The King James Translators Defend Their Use of Marginal Notes,” King James Bible History blogpost (March, 2020)

- Leonhard Schmitz, “Pontifex,” in A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, online version (1875)

- Sam Rainer, “Dispelling Four Common (and Unhelpful) Myths About Neighborhood Churches,” ChurchAnswers online article (October, 2023)

- William W. Combs, “Errors in the King James Version?,” Detroit Baptist Seminary Journal 4 (1999): 151–64

- Jared M. Compton, “Once More: Quirinius’s Census,” Detroit Baptist Seminary Journal 14 (2009): 45–5410

- W. Pouwelse, “Hal Lindsey: How Do We Study the Bible,” Spindle Works (1984), online article

- Willa Dale Smid, “Signs of the End of Time,” Spindle Works (1979), online article

- H.C. Hoskier, “The ‘Authorized’ Version of the 1611,” Bibliotheca Sacra 68.272 (1913): 693–70411

- Luther F. Dimmick, “The Spirit of Prophecy in Relation to the Future Condition of the Jews (part 1),” Bibliotheca Sacra 4.14 (1847): 337–69

- Luther F. Dimmick, “The Spirit of Prophecy in Relation to the Future Condition of the Jews (part 2),” Bibliotheca Sacra 4.15 (1847): 471–503

- Brian Jones, “Chuck Swindoll on Senior Pastors Being Themselves,” Senior Pastor Central blog (no date)

___________________________________

1 Not overly impressed. Not only danced around things a bit too much, but also presented ideas that bordered on unorthodoxy.

2 A full-on dismantling of Bart Ehrman’s attempts to dismantle Scripture and Christianity (and do so with old, tired, previously-proven-to-be-shoddy-arguments).

3 A cheeky title, because the book is about disproving the critics of the Bible who say there are corruptions in the text. Maybe a book Ehrman should have read.

4 An early (and biting) critique of the early form of Dispensationalism championed by Darby and the Plymouth Brethren.

5 A brief yet sufficient blow against critical scholarship, and a further indication that—when it comes to the claims, arguments, and opinions of critics—there is nothing new under the sun.

6 A well done and hard-hitting review of Bart Ehrman’s jaundiced (and deconstructionist) views of Christianity.

7 Did not do what he promised (in part 3) he would do.

8 NB: in the article, the author is incorrectly listed as “Hugh Ross.”

9 Not a convincing case, which is really odd, considering who made it.

10 A helpful little article in that it reminds current skeptics of the sufficient evidence against their claims.

11 A frustrating read of what amounts to an early example of the (ill-)logic of KJV-Onlyism.

can’t have it both ways

During my lunch, I was scrolling through random news headlines—just to see what’s going on…and to have more reasons to stop scrolling to see what’s going on—and I found a story about two potentially disgruntled super volcanoes. While reading, one section grabbed my attention. When dealing with the recent activity found in both super volcanoes, the writer said this:

Most experts say there is no immediate threat of an eruption at either Long Valley or Campi Flegrei. Both volcanoes are calderas — sprawling depressions created long ago by violent “super-eruptions” that essentially collapsed in on themselves — which are often more challenging to forecast compared to the large mountain-shaped features that people typically imagine when they think of volcanoes.

Let me see if I got this right: for the type of volcanoes that “are often more challenging to forecast”—meaning: it’s a crap-shoot on knowing whether or not they’re going to burst—the experts make the easy and definitive forecast that “there is no immediate threat of an eruption.” In the words of the philosopher Pete Hogwallop: “That don’t make no sense.” You can’t have it both ways. Or better: you can’t make those sorts of claims and expect them to be taken seriously.1

This is one of the reasons I don’t like reading news…

_________________________________________

1 And I admittedly struggle to take serious anyone who says something like, “You can have an impactful explosion at these places…”. I’m pretty sure a volcano’s explosion does the exact opposite of impact. So, can we stop using “impact” to describe nearly everything?

something’s missing… (part 3)

In part one of this series, we introduced the (bordering on) incendiary claims of the IG account, amazinggracecoffee concerning modern Bible translations. Claims of willful tactics among translators to corrupt Scripture by removing verses (and thus essential doctrines) from it. In part two, we focused on the bigger/more general problems with amazinggracecoffee’s claims—specifically, the three bits of detail that he leaves out (and doesn’t treat fairly). Omissions that don’t really help his case, but rather expose the structural weaknesses within it. (If you need a refresher on what’s been said, or if you’re encountering this post before the others, I encourage you to use the links provided and read those two before carrying on with this. Don’t worry, this content will be here waiting for you).

For this third part, we’ll to pick up where we left off in part two, but we’ll dig a bit deeper into the details involved. In particular, we’re going to explore more of the ancient manuscript testimony. This represents the promised (and needed) “more fine-tuned details.” And just to be clear: in describing things in that way, I’m not promising exhaustive coverage where every single little (sometimes niggly) detail about textual variants is explained. Something approximating that kind of work is currently underway through the efforts of the Institute for New Testament Textual Research (University of Münster) and their “Coherence-Based Genealogical Method” for textual criticism. What I’m offering here is a simple treatment and explanation of the essential details about the textual variants in Mt 17. A treatment that will be sufficient enough to reveal the problems (=baseless claims) in amazinggracecoffee’s IG reel.

Now, in the last post, we pointed out how amazinggracecoffee skips over the footnotes in the translations he criticizes. And in skipping over those notes, he’s able to make a claim about those translations that is not only misleading but also provably false. A claim that accuses the translators (or translation committees) of distorting the text of Scripture, and doing so with sinister (or conspiratorial) motives. But when we consider the notes (not to mention why they’re there and what they do), we easily realize how such an accusatory claim crashes hard on the cliffs of facts and evidence. To show where and how that’s the case is the focus of this post.

The sentence, τοῦτο δὲ τὸ γένος οὐκ ἐκπορεύεται εἰ μὴ ἐν προσευχῇ καὶ νηστείᾳ (“But this kind does not go out except by prayer and fasting”) is not found in a number of early NT manuscripts of Matthew’s Gospel. That’s a provable fact. (At least 16 manuscripts, ranging from the 3rd to the 13th century AD, lack the sentence). However, it is found in a number of later NT manuscripts. That, too, is a provable fact. (At least 250 manuscripts, ranging from the 3rd to the 15th century AD, include the sentence).1 Once again: that difference in the manuscript testimony is the very thing the footnotes in the criticized translations honestly express (but amazinggracecoffee ignores). They’re alerting the reader to the existence of a textual variant. Again, why would “they” do that? Conspiratorial people are not known for being honest with facts or evidence. But the translators of English Bibles are being honest about both.

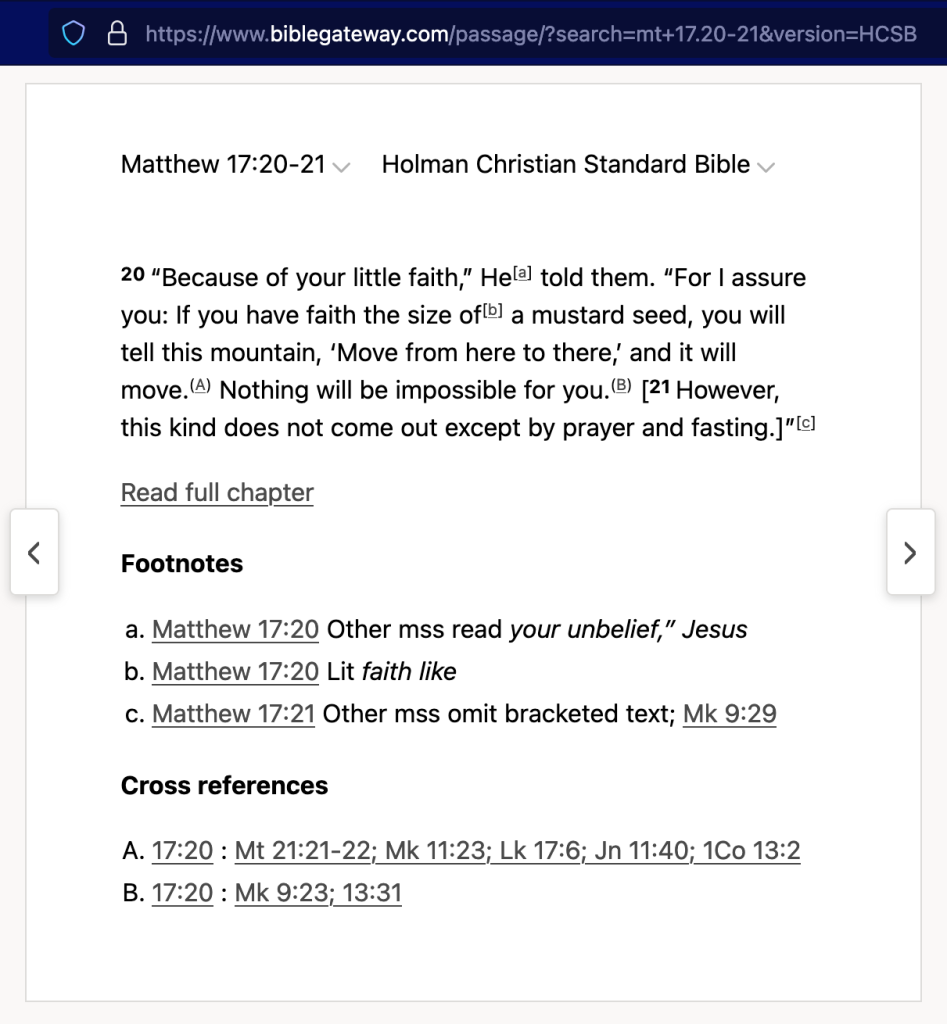

Moreover, the non-King James translations and/or versions that include what would be Mt 17.21 in the body of the text; they place the sentence in brackets to signal the insertion, and then provide a note that explains it.2 And quite often, that explanation refers to the parallel account of Mk 9.29. For example:

Now, to give a little bit of a heads-up: the footnotes’ appeal to Mk 9.29 is a key part of the solution for understanding why the sentence, τοῦτο δὲ τὸ γένος οὐκ ἐκπορεύεται εἰ μὴ ἐν προσευχῇ καὶ νηστείᾳ only appears in some manuscripts of Matthew’s Gospel and not others. Why that’s the case will be the focus of the next and final post in this series. Until then, there’s something else about the textual variant sometimes found in Matthew that cannot be overlooked. The sentence found in some manuscripts of Matthew’s Gospel is not exactly the same one found in other manuscripts. Thus, a “missing” verse is not the only detail one needs to recognize when dealing with the evidence.3

When it comes to what would be Mt 17.21, there are three main options for the text when it includes the sentence:

- τοῦτο δὲ τὸ γένος οὐκ ἐκπορεύεται εἰ μὴ ἐν προσευχῇ καὶ νηστείᾳ

- τοῦτο δὲ τὸ γένος οὐκ ἐξέρχεται εἰ μὴ ἐν προσευχῇ καὶ νηστείᾳ

- τοῦτο δὲ τὸ γένος οὐκ ἐκβάλλεται εἰ μὴ ἐν προσευχῇ καὶ νηστείᾳ

As we can see (helped by the bold print), these options differ only on one word. A verb. And in terms of general meaning, the differences are not overly significant. They tend to deal more with clarity of expression and/or intended effect (e.g., the difference between “move” and “shove”).

ἐκπορεύω carries the idea of making or causing something (or someone) to go out or come out from a given place. It’s a term used in military contexts to describe soldiers being marched out to do battle. ἐξέρχομαι gives the picture of moving from one place to another that is other than where one started. (This suggests more of a personal, voluntary choice about the movement). It’s also used in military settings, but typically for an army’s surrender in battle. And just for kicks: it’s even used for the birth of a child. And ἐκβάλλω is the more dramatic of the three, stressing the idea of something (or someone) being thrown or cast out from one place and into another. When it comes to the NT, this term is most often used in the context of casting out demons. (That will be important later…and right now).

But here’s something of an oddity that’s also a bit of a surprise. Given other uses of the term in the NT, especially when it comes to demons, and given that Mt 17.14–20 is about removing demons; one would think that the sentence-option with ἐκβάλλω would be the most common in the manuscript history. But it’s not. The one with ἐκπορεύω wins the day, and the one with ἐκβάλλω is dead last. Specifically, in the critical editions of the Greek NT, only one manuscript is listed: a later copy of Codex Sinaiticus—often referred to as, א2. And just to be clear: the “2” in this case is not a footnote reference, but the designation for a copy of the original codex.4 (<– that one’s a footnote). Two important details about this bit of evidence should be recognized.

First, the original text of Sinaiticus dates to c.mid-4th century AD. (Here’s an accessible treatment on this codex, which deals with its history and significance, and it allows you to see the text). When it comes to the date for the copy of Sinaiticus; I’m honestly not sure. I’ve seen ranges between early 5th to late 7th century AD. The range, however, makes one thing clear: the copy is quite a bit later than the original. And the second detail is: the original text of Sinaiticus lacks not only ἐκβάλλω but also the entire sentence that would be Mt 17.21. It’s the later copy of Sinaiticus that includes both—and does so as a footnote! To see for yourself, this link will take you to Mt 17 in Codex Sinaiticus. Once there, zoom in on the second column of text. About a third of the way down that column, on the left, is what looks like a tilted (and trippy) division symbol. That corresponds to the same symbol in the text, after the word YMIN (=ὑμῖν). And for what it’s worth: YMIN is the end of what we have as Mt 17.20. The very next word in Sinaiticus begins the sentence that corresponds with what we have as Mt 17.22. But, let’s get back on track.

The reference symbol (=marginal note) marks the addition of a variant reading. One that’s included more as a “headnote” than a footnote, because the content is found at the top of the page. And at the top of the page is the sentence that the later copyist added: τοῦτο δὲ τὸ γένος οὐκ ἐκβάλλεται εἰ μὴ ἐν προσευχῇ καὶ νηστείᾳ. That added reading is what sometimes makes its way into some translations at what we would call Mt 17.21. (The likely reasons why will be discussed in the next post). All of this is one of the leading reasons why the CSB and NIV (not to mention quite a few others translations and/or versions) have the footnote in modern Bibles that says: “some mss include…” or even “some mss omit…”. Thus, and contrary to what one commenter on the reel believed: the footnotes are not spreading lies. They’re making simple, honest statements of fact about the ancient evidence—i.e., it’s a provable fact that some manuscripts have the sentence and others do not. And Codex Sinaiticus (along with its copy) is a testimony of that reality.

Now, here’s why this footnoted (or “headnoted”) reading in Sinaiticus is important. And this gets us back to the underlying, yet core assumption mentioned in the last post (i.e., the assumption about original readings of the text). In the reel, amazinggracecoffee draws explicit attention to the fact that the CSB and NIV move from Mt 17.20 to Mt 17.22 as though it’s a continuous reading. And from that detail, he concludes there’s a conspiracy among the translators (or translation committees) to do this skipping-over because “they” don’t want what Mt 17.21 says. And because “they” don’t want the teaching known, “they” have deleted the verse that was originally in the text of Scripture that affirmed the teaching. And what’s his proof that Mt 17.21 is original to the text and that modern translators have deleted it? The verse is found in the KJV. And because the KJV has it, it must have been original. Here’s where I need to be lovingly direct.

Not only has amazinggracecoffee been wrongly encouraged to make the (supposed) culprits relatively modern, he’s also been misled into the unfounded beliefs about textual priority—not to mention what translations ought to be accepted as the standard for knowing the original text. (And that, too, is not a new mentality or problem. There are 5th and 16th century examples of its misleading activity in people’s minds about the text of Scripture). While we can easily get stuck in the briars (or minefield) of that topic, let’s focus on what’s relevant here. The observation about a supposed “missing verse” in Mt 17 is not modern. It’s been had and known about for many centuries. Thus, amazinggracecoffee is not pointing out anything new, groundbreaking, game-changing, or any other of the silly, overused catchphrases employed to gain attention and acceptance of what’s being said (or sold). Knowledge of these kinds of textual variants is ancient, and they have been settled for many, many generations.

Also, a supposed “missing verse” in Mt 17 is not the work of modern, nefarious translators hell-bent on changing (or destroying) God’s Word. The original of Sinaiticus (4th century AD) shows the absence of what would be Mt 17.21. As mentioned already: that text moves from what we would call Mt 17.20 to Mt 17.22. Just like what’s found in CSB, NIV, and a number of other translations. Translations that are simply following the evidence—as found, for example, in Sinaiticus. An ancient text that’s understood to be one of the earliest and better-attested “complete” manuscripts for reconstructing the original text of Scripture (especially the NT).

And Sinaiticus is not the only one that speaks to this detail about Mt 17. There is also the 4th century AD Codex Vaticanus, which is another early, vital manuscript for reconstructing the original text of Scripture. But there’s a notable difference between it and Sinaiticus. Vaticanus lacks not only what would be Mt 17.21 but also any noted, scribal addition (you can see for yourself here: middle column, about half way down). And similar things could be said for at least 16 other ancient manuscripts, ranging from the 3rd to the 13th century. They all testify to the lack of what we would call Mt 17.21. (What we do with the larger manuscript testimony that includes the sentence will be discussed in the next post).

“To make a long story short…” “Too late”:5 these facts, based on the evidence about the text of Scripture (and its transmission history), are what prompts the footnotes in English translations to say, “some mss include…” or “some mss omit…”. And it’s these facts and evidence, especially about the footnotes, are what amazinggracecoffee either downplays and portrays badly or just flat-out ignores. especially evidence that conflicts with not just the text of the KJV but particularly one’s beliefs about the KJV. Thus, amazinggracecoffee’s claim illustrates the kind of treatment that’s often used to criticize and shame certain English translations (that are provably being honest about the facts) so as to exalt a particular and more favored translation: the KJV (and doing so without facts or evidence, but relying on bad assumptions and conspiracy theories).

But I wonder what amazinggracecoffee would say if he knew that the KJV translators provided notes (and marginal readings) about places where they knew about differences in the manuscript history—either in words or entire phrases? Places like: 1 Chr 1.6–7; Ezra 2.33; 10.40; Mt 26.26; Lk 10.22; Jn 18.13; Acts 25.6; Eph 6.9; or 2 Jn 1.8. Places where the KJV translators honestly admit: “many ancient copies add,” “[X difference] in some copies,” or “some copies reade.” No matter the description, it all means the same thing. They’re saying: “There is a known variant in the textual transmission history at this point in the text, and we’re alerting you to it.” (And I wonder what amazinggracecoffee would say about the variant readings footnoted in the [non-canonical] Apocrypha section of the KJV…?—e.g., 1 Esd 5.25; 8.2). But more to the point: I wonder what amazinggracecoffee would say about the KJV’s treatment of Lk 17.36, which reflects the same type of issue found in non-KJV treatments of Mt 17.21?

The KJV for Lk 17 reads, “35 Two women shall bee grinding together; the one shall be taken, and the other left. 36 Two men shall be in the field; the one shall be taken, and the other left. 37 And they answered, and said vnto him, Where Lord? And he said vnto them, Wheresoeuer the body is, thither will the Eagles be gathered together.” At the start of v.36, there is a marginal note about a textual variant. The note says, “This 36 verse is wanting in most of the Greek copies.” This means: the KJV translators are giving readers a heads-up to the reality that, “in most of the Greek copies,” the text moves from what we call v.35 to what we call v.37. The KJV translators are honestly admitting that, “in most Greek copies,” v.36 is missing. The KJV translators are doing the same thing that translators of more modern translations (or versions) are doing with Mt 17.21.6 And yet it’s the more modern translations (or versions) that are being criticized (if not demonized) for changing the Bible.

But, and to close out this post, let’s ask a rather basic question about the admission in the KJV on the variant in Lk 17. Why did they recognize and note the variant in there (and quite a few other places) but not the one in Mt 17? The short answer is: not only did the KJV translators not seek to create a translation from scratch (working from the original Hebrew and Greek texts), but they also did not have (or use) an available wide or deep base of manuscript testimony from which they could recognize all the variants when they occurred. This is not to say their evidence was poor or corrupted. It’s just saying: they didn’t have that much available to them. They certainly did not have what we have now. For the NT (since it bears on this post), the KJV translators had:

- the Greek text compiled by Erasmus, who, by the time he completed his third edition (in 1522), used 11 Greek manuscripts (ranging from the 9th to the 16th century, with the bulk coming from the 12th century)

- the Greek text complied by Stephanus (=Robert Estienne), who, by the time of his third edition (in 1551), used Erasmus’ third edition and added notes/revisions based on 16 additional manuscripts (ranging from the 5th to the 16th century, with the bulk coming from after the 11th century)

- the Greek-Latin parallel text compiled by Theodore Beza (in 1565), who relied primarily on Stephanus’ third edition and barely upon readings found in two additional manuscripts (coming from the 5th and 6th centuries), and

- the Latin Vulgate—mainly the one supplied by Erasmus in his third edition, which was effectively a parallel Bible.

Thus, the KJV translators—when they consulted the Greek text—were operating from a textual base of 39 ancient manuscripts. And the bulk of those were (comparatively) not all that ancient when they were used by Erasmus, Stephanus, and Beza.

But here’s the point to the question about Lk 17 and Mt 17. Within this available manuscript testimony, the variant readings for Lk 17 are present; but the variant readings for Mt 17 are not. Instead, for Mt 17, the fairly limited and fairly late testimony of this textual base would suggest to them that what exists as Mt 17.21 is “original” to the text. They simply did not have the evidence from earlier manuscripts—e.g., Sinaiticus, Vaticanus—because such texts had not yet been found. If the KJV translators had these ancient manuscripts, which considerably predate what Erasmus had available to him (manuscripts that show Mt 17.21 to be missing from the earlier manuscript testimony), I’d be willing to bet they would have (at the very least) made a note in the margin. Just like they did in Lk 17. They would have been honest about the facts, based on the evidence.

In the fourth and final part of this series, we’ll focus on the likely reasons why the variant reading in Mt 17 happened. And to do that, we’ll have to consider the text of Mk 9.29, which also contains an intriguing variant in the ancient manuscript testimony…. See you then.

_______________________________________

1 It’s worth pointing out that, when it comes to textual criticism and weighing the merits of variant readings, the decision cannot be based on the number of manuscripts that testify about a particular variant. The process involved for deciding a variant is far more involved and meaningful than that.

2 See e.g., AMP, EXP, HCSB, ICS, LSB, NASB95, NCB, NCV. It’s also worth mentioning that some translations will include the words without brackets but provide a note—see e.g., EHV, ISV, TLB, NLV, WEB. And there are some that will include the words without brackets and without an explanatory note—see e.g., AV, BRG, Darby, GNV, Phillips, JUB, KJV, MEV, NKJV, NMB, OJB, RGT.

3 NB: in pointing out this extra detail, I am not claiming the translators (or translation committees) missed it, think it’s irrelevant, or are engaged in more conspiratorial tactics by not mentioning it. This extra detail is one that represents a kind variation in the textual history that does not require a footnote, because the difference (in this case) is not as affecting as others—i.e., some manuscripts have an entire sentence and others don’t.

4 Admittedly, using א to refer to Sinaiticus reveals my “default” thinking on how manuscripts are identified. It’s simply the result of how I was taught NT Greek and textual criticism. It’s proper designation is GA 01.

5 Props to those who know the source of that quote, without having to Google it.

6 It’s also worth mentioning that the KJV translators were following a similar practice for noting variants as found in the existing Bibles they used as a base for their version—e.g., the Great Bible (1539) and the Bishop’s Bible (1568).

something’s missing… (part 2)

*apologies for my delays in posting. Family and ministry needs took priority.

In part one of this series, I mentioned the claims of the IG account, amazinggracecoffee concerning “missing verses” from the Bible. Specifically, the charge that (some nefarious) “they” have deleted Mt 17.21 from certain Bibles—because they’re afraid of the power of fasting (…or so it’s believed). I ended that post by saying there are some problems with the reel’s claims—not to mention its rhetorical intent (and effect). This post will focus on the bigger/more general problems, and the next two posts will deal with some of the more fine-tuned details. So, be sure to check back for those. To remind ourselves of what’s going on, here is the content of what’s claimed in the reel:

Certain Scriptures are missing out of different Bibles. So, we had to check our Bibles. Christian Standard Bible. This verse is Matthew 17:21. And on this one, it goes from straight from 20 to 22. It does not have 21. So, a new NIV and Matthew 17:20, right over 21 to 22. This is my Bible: King James Version. Matthew 17:21, of course, is there: “Howbeit this kind goeth not out but by prayer and fasting.” This is my mom’s Bible from way back when. Matthew 17, I said it’s probably underlined and sure enough: “This kind goeth not out but by prayer and fasting.” So, the conspiracy theory is that there is so much power in prayer and especially fasting that they’re leaving it out of the Bibles. Check your Bible folks.

Let’s start with the rhetorical intent (and effect). In 1min 16secs, using just over 130 calmly spoken words, amazinggracecoffee makes his point. Easily watched, heard, and received. The key ingredients not only for a good social media post but also to ensure shareability to help spread the word. (Or in this case: the “conspiracy theory”). Now, to be sure, a quick-fire response or rebuttal could easily be created. And I honestly thought about making and posting a remix reel on IG. But a quick-fire response or rebuttal can easily fall into the same problem as the original post—i.e., it becomes a case that lacks nuance or the needed explanation. And that lack is another problem with the original reel. Pertinent information is missing. (Dare I say left out?) Or to be blunt: amazinggracecoffee is not being fair with what he claims. And that’s the focus of this post, which deals with three bits of info he leaves out.

First: it’s true that the CSB and NIV skip over what would be Mt 17.21.1 And the same is the case with 20 other English translations and/or versions.2 But it’s also true that the CSB and NIV have footnotes at the end of Mt 17.20.3 In fact, the footnotes can be clearly seen in the reel. But amazinggracecoffee breezes right past that detail. Why? I don’t know, and I’m not going to speculate. However, I will say this: if he took the extra moment to consult them, he would find that, in both cases—not to mention in nearly all of the 20 other translations or versions4—the footnote says (as it does in the CSB): “some mss include v.21: ‘However, this kind does not come out except by prayer and fasting’.” That clear detail begins to hurt the claim about some conspiratorial decision by the translators (or the translation committee) to corrupt God’s Word by deleting Scripture. The footnote openly and honestly admits to the existence of differences in the ancient manuscript testimony. Why would “they” state that fact?

Before considering the ancient testimony, there is a second bit of info amazinggracecoffee overlooks and doesn’t portray fairly. While the sentence, “But this kind does not go out except by prayer and fasting”5 is absent in Matthew’s Gospel, it’s not absent from the Bible (as the reel suggests). Proof? Check out Mark 9.29, which is a part of the obvious parallel account of Mt 17. And once more: if amazinggracecoffee took the extra moment and consulted the footnotes he skips over, he’d find that a number of English translations and/or versions bear witness to that reality.6 In fact, the (updated) NIV’s footnote at what would be Mt 17.21 says: “some manuscripts include here words similar to Mark 9.29.” Again, they’re being honest about the facts. Thus, the accusation of conspiratorially “deleting scripture” is proving to be baseless, unconvincing, and silly. If “they” truly wanted to remove a teaching from Scripture, why did “they” (supposedly) delete it from Matthew but leave it in Mark? Also, it’s not a very good conspiracy if “they” put a footnote that effectively says: “some manuscripts don’t have certain words in Matthew’s account at this point, but Mark has them; and here’s where you can find them.”

That brings us to the third bit of info—one that we can only introduce in this post: the ancient manuscript testimony. While some resist this topic (for various reasons—some, not so good), it’s essential to the discussion. Partly because an underlying, yet core assumption within amazinggracecoffee’s (admitted) “conspiracy theory” is that what’s (supposedly) “deleted” from Matthew was originally included in that Gospel. But the assumption of original-ness is never proven to be true. There is no interaction with the evidence (i.e., the ancient manuscript testimony), either to test it or temper it. And it’s evidence that amazinggracecoffee doesn’t seem to know, doesn’t want to know, or doesn’t want others to know, so that they can test or temper the assumption. I’m not sure which is the case, but neither is good. Either way, the evidence that’s not being considered is the evidence that creates serious problems for the assumption.

In “part 3” of this series, we’ll give our attention to that evidence and see why it creates problems for amazinggracecoffee’s assumptions, claims, and conspiracy theory.

__________________________________

1 It must be remembered that chapter and verse numbers are later additions to the biblical text—i.e., they were not original.

2 See e.g., ASV, CEB, CJB, CEV, DLNT, ERV, ESV, GW, GNT, LEB, NOG, NABRE, NASB, NET, NIrV, NIV, NLT, NRSV, RSV, TLV. Just for what it’s worth: the older Catholic version—the Douay-Rheims, 1899 American edition—includes the sentence, “But this kind is not cast out but by prayer and fasting,” but has it as v.20 instead of v.21. In fact, reading back through Mt 17 shows the verse-numbering becomes different (by one) at v.14. Why it does that, I have no idea. If someone knows, I’m all ears to learn.

3 In response to a comment that recognizes the footnote in the text on Mt 17.21, someone quickly fired back: “the foot notes [sic] are a lie. Do your research for yourselves and stop trusting the stupid scholars. KJV is inerrant. Look up Psalm 12:6-7 and compare between NIV and KJV. It will reveal the lie!!!! Genesis 3:5 YEAH, Hath God said? Satan wants you to doubt Gods [sic] word, his deceit hasn’t changed in 6000 years.” There is so much wrong with this sort of claim. He provides no evidence or examples for how the footnotes lie. He just makes the assertion and we’re supposed to believe him. He uses ad hominem tactics to give weight to his case—i.e., “stupid scholars.” But such tactics are nearly always employed by those who don’t have a legitimate argument to make about the facts. He declares the KJV to be “inerrant,” which is not only patently (and definitionally) false—and provably so—but also ignorant of the facts. In the Preface to the KJV, the translators make it quite clear that they never once claimed nor ever once thought their completed work to be inerrant. He offers Ps 12.6–7 as proof of not only the KJV’s inerrancy but also that the footnotes lie. But here’s what happens when we check the comparison between the NIV and KJV that he suggests. The NIV has a note about a textual variant between the original Hebrew and the Masoretic text at the end of v.6, whose meaning is “probable.” So, I’m not sure how a lie is being championed and foisted upon an unsuspecting readership. A lie that the dude compares with Satan’s tactics in Gen 3.5. But he never proves the comparison (which can’t be done anyway because the evidence is not in his favor); he, once again, just asserts the connection and expects people to believe him. And he claims that Satan’s schemes of deceit and corruption of God’s Word have not “changed in 6000 years.” That raises a question: what has Satan been doing since that time? I ask because 6000 years might get you from the Garden to Abraham. Those problems aside, what’s a bit more disturbing, yet typical of staunch KJV only advocates, is the double-standard. Footnotes in other translations are lie, but footnotes in the KJV are given a free pass. Scholars who created other translations are “stupid,” but the scholars who created the KJV were essentially inspired and inerrant. Other translations with textual variants are wrong, but the KJV is exempt.

4 NIrV is the only one that excludes the verse without an explanatory note. But that might simply be due to the choice of the publishers to avoid using notes.

5 The eagle-eyed among you might have spotted a couple of things about this rendering vs. the one given in the CSB footnote (and even the reading given in the Douay-Rheims, in n.2 above). Hang on to that observation. It will be important later.

6 21KJV, AMP, DARBY, EHV, GNV, HCSB*, ISV, JUB, KJV, MEV, NCB*, NKJV, RGT, RSVCE, WE, WEB, WYC, YLT. The * with two of the translations listed indicates a footnote in the text about the reading found in Mk 9.29.

something’s missing… (part 1)

I recently stumbled upon an Instagram reel from “amazinggracecoffee” with the static header: “Now they’re leaving verses out of certain bibles. Matthew 17:21.” Sounds ominous and concerning, indeed. Especially for those who wish to ensure that God’s Word remains unchanged. After all, as it’s often pointed out, Revelation warns that “if any man shall take away from the words of the book of this prophecy, God shall take away his part out of the book of life, and out of the holy city, and from the things which are written in this book” (Rev 22.19, KJV). So, “leaving verses out of certain Bibles” can’t be good—especially for the ones doing it.

That, then, raises a basic question: who is the “they”? A seemingly good piece of information to know, particularly if we need to hold them accountable or at least avoid them. While the reel’s description doesn’t offer a clear answer to the question, it does provide a starting point. It says, “Check your new Bibles! Call the publisher if you find deleted scripture!” So, at the very least, that seems to mean we can rule out the publishers as being the “they,” since they’re presumably the ones who can help fix the “deleted scripture” problem. That would also mean the nebulous (and nefarious) “they” must reside somewhere outside of publishing houses. Possibly in dark alleys that ought to be avoided.

But the question remains: Who are “they” that hide in dark places and do bad things to Bibles? The closest thing that comes to identifying them, as well as attempting to prove the claim that “they’re leaving verses out of certain bibles,” is found in what amazinggracecoffee says. To set the scene (since I couldn’t link the reel to this post): in the video, we see a kitchen counter with multiple open Bibles on it. Four, to be precise. We also catch brief glimpses of a young lady—I’m not sure what the relation is—who’s in support of what’s being said. As the video unfolds, for 1min 16secs, the gentleman goes through the Bibles in sequence and points out the place where he has concerns. Here’s what he says:

“Certain Scriptures are missing out of different Bibles. So, we had to check our Bibles. Christian Standard Bible. This verse is Matthew 17:21. And on this one, it goes from straight from 20 to 22. It does not have 21. So, a new NIV and Matthew 17:20, right over 21 to 22. This is my Bible: King James Version. Matthew 17:21, of course, is there: ‘Howbeit this kind goeth not out but by prayer and fasting.’ This is my mom’s Bible from way back when. Matthew 17, I said it’s probably underlined and sure enough: ‘This kind goeth not out but by prayer and fasting.’ So, the conspiracy theory is that there is so much power in prayer and especially fasting that they’re leaving it out of the Bibles. Check your Bible folks.”

With such visible and verifiable evidence presented in this way, amazinggracecoffee seems to make an easy case against those who are “leaving verses out of certain bibles.” And from that, we can know that the “they” at least refers to specific Bible translations—or, if pressed, the translators (or the translation committees) responsible for those translations. Moreover, with the visible and verifiable evidence presented in this way, amazinggracecoffee seems to be able to make a solid case for the KJV—since it is obviously the translation that’s not “leaving verses out” of God’s Word,1 thus making it more reliable and therefore more trustworthy.

And given all of that, plus the brevity of the reel (along with the appeal to conspiracy theories), I wouldn’t be surprised if it results in a slew of likes, shares, and supporting amens—if not calls to do away with translations other than the KJV.2 However, there are some key problems. With all of it. And not just the details of what’s said in the reel, but also the intended effect. In part of two of this series, I’ll explain what those key problems are.

________________________________

1 This is said with a little bit of tongue-in-cheek. It’s a point that will need to be tested with facts.

2 After watching the reel, I did have a quick peek at the comment section (…always a risky move), and one of the early ones said, “Just wait until they find out there’s [sic] whole books missing,” which I’m suspecting is a jab from across the river. And another said, “I’m in shock, mine does not have it” (referring to Mt 17.21). “Which also makes me wonder, what else is missing??? What Bible do you recommend please???”

reading list of 2022

I’m a couple of days late in posting this, but hey: it’s better than a couple of years. I also fell a bit short of my expected goal for the year—i.e., I try to read anywhere between 40-50 books a year. I hit half, on the low end. Shame on me. But, there’s always 2023. In the meantime, here’s the list from 2022:

Books (and booklets)

- Eric van Lustbader, The Bourne Ascendancy (2014)

- Stephen Bedard, The Watchtower and the Word (2014)

- John Grisham, The Rogue Lawyer (2016)

- P.G. Wodehouse, Mulliner Nights (2005)

- Moliere, Eight Plays (1957)

- Plutarch, The Rise and Fall of Athens (1960)

- Eric van Lustbader, The Bourne Enigma (2016)

- Joshua Hood, The Treadstone Resurrection (2020)

- Douglas Corleone, The Janson Equation (2015)

- Tom Clancy & Peter Telep, Against All Enemies (2011)

- Kyle Mills, The Utopia Experiment—A Covert-One Novel (2013)

- Jamie Freveletti, Geneva Strategy—A Covert-One Novel (2015)

- Kyle Mills, The Patriot Attack—A Covert-One Novel (2015)

- Eric van Lustbader, The Bourne Initiative (2017)1

- Gerald C. Traecy, After Death—What? Heaven, Purgatory, Hell (1927)2

- D.L. Moody, How to Study the Bible (2017)

- Donald Whitney, Praying the Bible (2015)

- R.C. Sproul, Why Should I Join a Church? (2019)3

- Roland Bainton, Here I Stand. A Life of Martin Luther (1950)

- Voddie Baucham, Fault Lines. The Social Justice Movement and Evangelicalism’s Looming Catastrophe (2021)

Articles, Essays, etc.

- G.R. Beasley-Murray, “The Second Coming in the Book of Revelation.” Evangelical Quarterly 23.1 (1951): 40–45

- Timothy Berg, “Seven Common Misconceptions about the King James Bible.” Text & Canon Institute, web-article (22-Feb-2022)

- Timothy Berg, “The KJV Copyright: A Sordid Take of Intrigue and Avarice.” King James Bible History, blog post (27-Mar-2020)

- Caroline E. Janney, “War Over a Shrine of Peace: The Appomattox Peace Monument and Retreat from Reconciliation.” Journal of Southern History 77.1 (2011): 91–120.

- Anthony C. Garland, “Does Dispensationalism Teach Two Ways of Salvation?” Conservative Theological Journal (2003)4

- Scott K. Leafe, “Understanding Dispensationalism.”5

- Timothy Berg, “The Not-so-Exact King James Bible.” Text & Canon Institute, web-article (26-Mar-2020)

- Edwin M. Yamauchi, “Archaeological Backgrounds of the Exilic and Postexilic Era, Part 1: The Archaeological Background of Daniel.” Bibliotheca Sacra 137 (1980): 1–16.

- Edwin M. Yamauchi, “Archaeological Backgrounds of the Exilic and Postexilic Era, Part 2: The Archaeological Background of Esther.” Bibliotheca Sacra 137 (1980): 99–117.

__________________________________

1 Not as bad as his immediately preceding volumes, but not as good as his earlier ones.

2 A mercifully brief read that was just poorly argued right the way through, and then, at the end, came within a breath of committing blasphemy.

3 Expectedly Reformed in its approach, but the title is a bit misleading. The book doesn’t really answer the question. It’s more descriptive than explanatory. In fact, given the substance and content, it almost didn’t need to be written, for the details covered would have fit nicely in Sproul’s 2013 volume, What is the Church?. And if memory serves me right (since I read it back in 2017), much of the detail from the 2019 volume was covered in the 2013 one. And regrettably, one of the details in both is the commonly held ridiculous and exegetically fallacious claim that, on the basis of the parts, ἐκ = “out (of)”, καλέω = “I call,” the term for “church” (ἐκκλησία) means “called out ones.” It doesn’t. That was a view popularized by C.I. Scofield in the early 1900s. And getting Greek instruction from Scofield is like getting theology from TikTok. Just not a good idea. Historically, ἐκκλησία means: assembly, gathering, community, congregation, and (later) church.

4 Painfully and poorly argued.

5 Also painfully and poorly argued.

snarky but true

From my morning reading:

“Too many contemporary evangelicals believe we have only two views of Revelation: their own view and the liberal view.” (K.L. Gentry, Navigating the Book of Revelation [2011]).